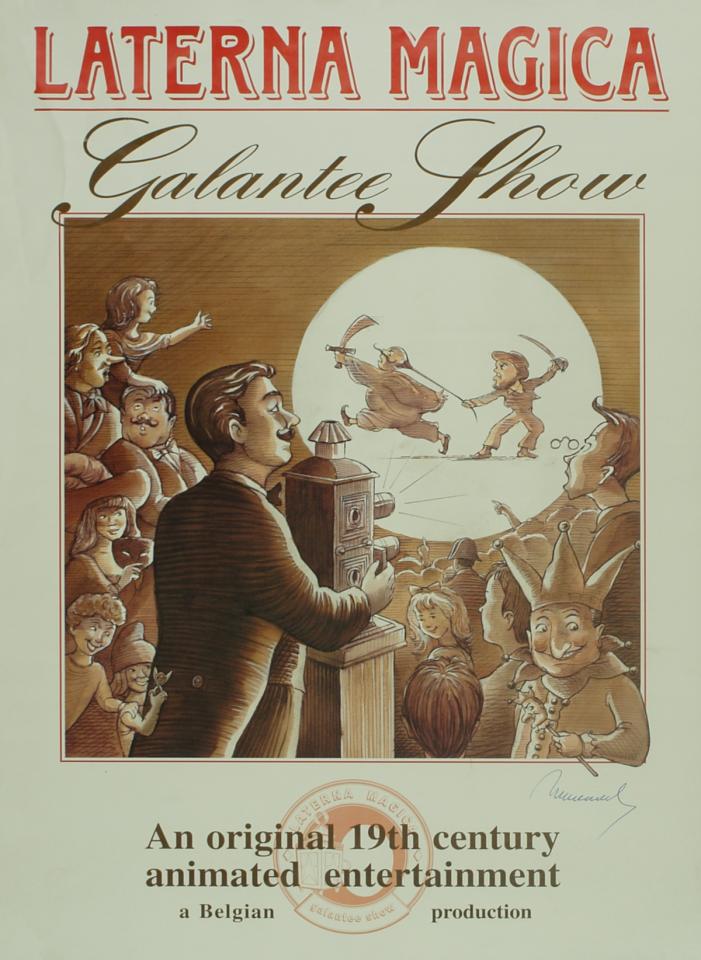

Laterna Magica Galantee Show. An original 19th century animated entertainment, Collectie Stad Antwerpen, Letterenhuis, inv. 43277

A very recognisable but partly forgotten ‘modern’ form came with the magic lantern or laterna magica, invented as early as the 17th century by the Dutch astronomer Christiaan Huygens. It would take until the 19th century before this lantern enjoyed widespread popularity, first thanks to itinerant travellers who performed lantern shows at fairs, inns and in pubs.

Thanks to simpler, cheaper models, the magic lantern soon became a sought-after Christmas or St Nicholas gift for children to play with at home. Finally, new developments ensured that light projection also found its way into education.

In the first half of the 20th century, the latest technological feats initially reinforced the optical lantern, but gradually shunted it out as well. The magic lantern became inferior to the slide projector and film and ended up, together with the glass slides, in attics and museums.

Child's play

A remarkable sub-collection of the MAS consists of some 765 toy magic lantern slides. They have already been made accessible online.

The oldest magic lantern slides found in the MAS collection probably date from the early 19th century. They are attributed to Johann Christian Wolfgang Rose (1769-1826), a Nuremberg manufacturer of optical toys like the magic lantern and other optical instruments, including the camera obscura. Rose's glass slides are characterized by unique hand-painted drawings and a border checked with red lines.

Johann Christian Wolfgang Rose, Magic lantern slide with fantasy representation of a noble woman whose carriage is pulled by a partridge, VM.2009.101.039.001, Collection City of Antwerp, MAS

Johann Christian Wolfgang Rose and his father Johann Friedrich were the predecessors of a whole host of manufacturers of toy lanterns and accessories. All settled in Nuremberg around 1900 and made a name for themselves there. Instead of painting the glass slides by hand, they often used decalcomania, an automated process that ‘stuck’ the image onto the glass in mirror image.

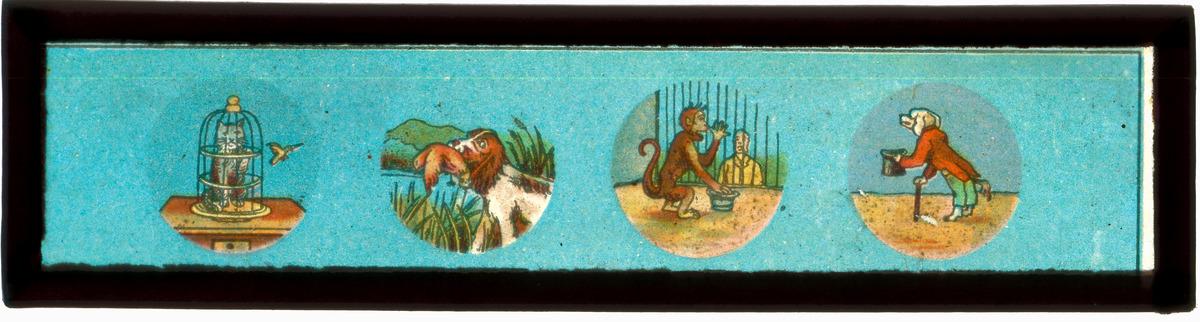

Gebrüder Bing (Nürnberg), Magic lantern slide with fantasy representation of the life of a frog, VM.2008.327.020.011, City of Antwerp collection, MAS.

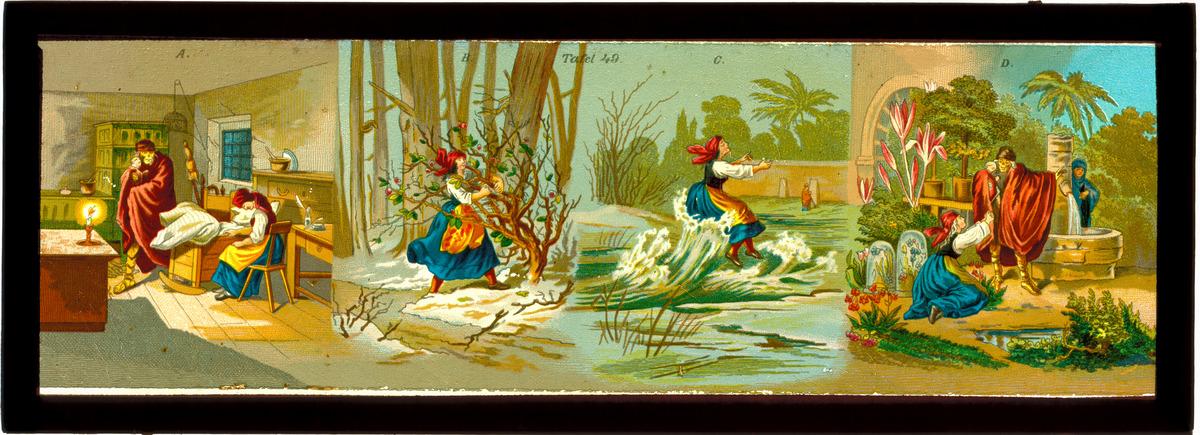

Georges Carette & Co., Magic lantern slide depicting the fairy tale ‘The history of a mother’ by Hans Christian Andersen, VM.2008.327.023.001, City of Antwerp collection, MAS

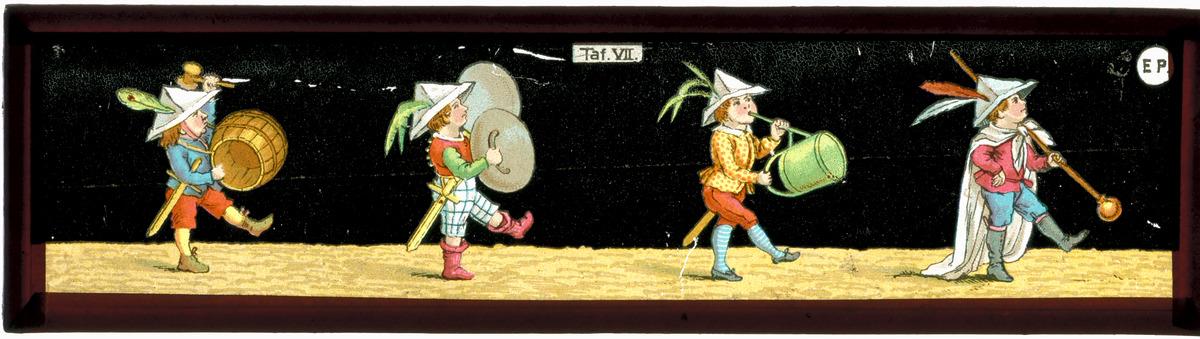

Ernst Plank KG, Magic lantern slide showing an improvised brass band, VM.2008.327.019.010, City of Antwerp collection, MAS

These oblong slides are easily found in the MAS collection online and were used as toys at home. Although sometimes moralizing, the playful nature of the content prevailed. Common were comic scenes, humanized animals, fairy tales and satirical caricatures. The colourful pictures stimulated the imagination of countless children. Like the Antwerp writer Victor J. Brunclair (1899-1944), who in 1909 spent hours on his little elder in the Seefhoek with a toy magic lantern. He summed it up blissfully-nostalgically in 1940 as follows: ‘Camels [sic.] in a yellow sand desert. A monkey on a bicycle. A lad with a hoop. A seal with a ball.’

Johann Falk, Toverlantaarnplaat met fantasievoorstelling van dieren, VM.2008.327.019.183, collectie Stad Antwerpen, MAS

Instructive

Another MAS sub-collection of slides differs from the aforementioned toy lantern slides in that they were intended for education.

Whereas the magic lantern initially served mainly to provide entertainment, from the end of the 19th century the optical lantern also took on a distinctly educational function. The Catholics used to have a monopoly on education in Flanders, but that came to an end when the Liberals also started to develop a school network, with the natural sciences as an important addition to the curriculum. Scientific observation took centre stage, a shift that eventually brought about a profound change in pedagogy. (Nelleke Teughels spoke about this on 18 September 2021 in the radio programme 'Interne Keuken' on Radio 1. She is part of B-Magic, a group of interdisciplinary researchers looking into the history of the magic lantern as a mass medium in Belgium).

Of the loosely estimated 9,000 educational glass slides managed by the MAS, by far the largest part comes from the former Stedelijk Schoolmuseum in Antwerp. This had an extensive collection of glass positives that were accessible to teachers through the loan service. As curator of the Stedelijk School Museum, Hendrik Van Tichelen was a significant driving force in acquiring and documenting these visual teaching aids.

From about 1923, Antwerp schools made use of the lending service and by 1934 the collection of the Municipal School Museum had grown to about a thousand series, accounting for more than 20,000 slides or ‘light images’ in total. At least half of these have been preserved and are today scattered in the collection of the MAS and the FelixArchive. Digitization of these glass slides has started, but will take a lot of time.

The educational slides differ both in form and content from the toy slides. This is also because they are no longer just drawn images, but also black-and-white photographs. Although often a pose or even exaggerated acting, these photographic glass positives are usually closer to more reliable representations of reality than the toy slides. We do still note thematically a strong representation of fairy tales and more extensively children's literature, but in addition, for instance, images of workers demonstrating their work in the factory or workshop and photo series of public events or famous places are commonplace.

Radiguet & Massiot, Glass positive with black-and-white photograph of a millinery: workers make the straw hats, MF.1962.078.0769, City of Antwerp collection, MAS

Radiguet & Massiot, Glaspositief met zwart-witfoto van een hoedenmakerij: arbeidsters boorden de hoeden af met lint, MF.1962.078.0774, collectie Stad Antwerpen, MAS

Pre-cinematographic glass slides have been a big step towards an increasingly cosmopolitan society where visual culture influences all areas. At school, students could watch projections of volcanic eruptions, other continents or animals you would never encounter in everyday life, without leaving their couch. This inevitably contributed to the worldview of many generations and lives on to this day in ever-changing forms.

This article you read on your PC, laptop or smartphone also includes accompanying images to make the text tolerable. A hundred years ago, this was quasi-unthinkable and people shared images in all sorts of other ways. Lantern slides have been a crucial link in the retrospectively unstoppable and lightning-fast breakthrough of mass media such as film, television and computers. They testify to the persistence of human inventiveness and are an indispensable and undeniable part of our cultural history and heritage. Not only are slides interesting as a medium, but also as a time document. By preserving them, we guarantee for now and tomorrow a better understanding of the ideas, visual trends and themes with which children grew up in the 19th and 20th centuries.