Provenance Research

In the region that is now the Democratic Republic of the Congo, countless cultural objects were taken during the colonial period (1885–1960). This happened in a context of colonial power dynamics and violence. Many objects were surrendered under coercion and then shipped to Antwerp, where they ended up with collectors and in museums. Through various routes, they eventually found their way to the MAS. Today, the museum manages around 3,800 of these objects, which have lost their connection to their communities of origin.

The MAS investigated the provenance of these objects and the circumstances under which three key pieces were taken from their original owners. The publication is the result of this in-depth study, conducted from a Belgian-Congolese perspective, which the MAS aims to share transparently with a broad audience in Belgium, Congo, and beyond.

Value for the Future

This report highlights not only the history of the collection but also the value it still holds today for Congolese artists and communities. The knowledge it generates is highly relevant, not only for the ongoing dialogue about the future of the collection but also for processes of repair.

The new publication On Origins and Futures (200 pages, bilingual Dutch/French) brings together the provenance research carried out at MAS by Els De Palmenaer (curator of Africa at MAS), Prof. Donatien Dibwe dia Mwembu (Congolese project leader and researcher, UNILU Lubumbashi), and Bram Cleys (Belgian project leader and researcher), with fieldwork by three Congolese researchers: Philippe Mikobi Pongo, Dieudonné Kabuetele, and Constantin Kasongo Kitenge.

Publication

You can download or view the publication below (in Dutch or French).

Three Key Pieces

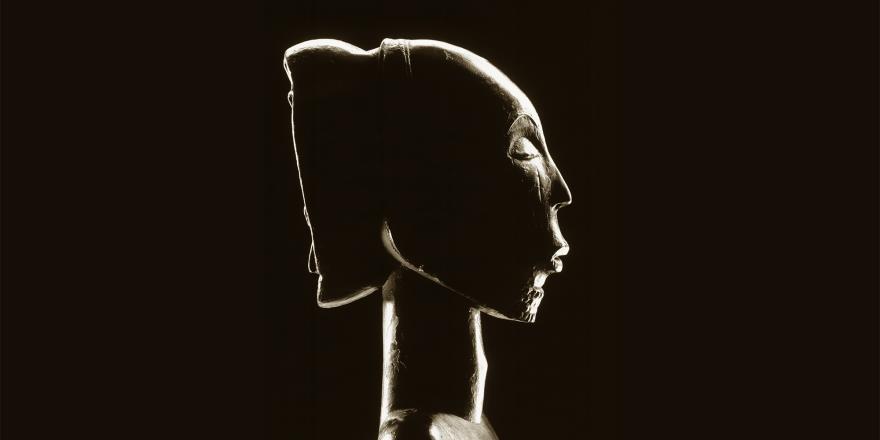

The three key pieces examined each demonstrate, in their own way, how Congolese heritage disappeared from its communities within a colonial context. Not all details can be recovered, but the research has led to new insights and to collaborations with Congolese communities and researchers.

- The power figure (nkishi) of Chief Nkolomonyi belonged to a Songo Meno chief who resisted the colonial occupation. After his arrest in 1923, his possessions — including this figure — were confiscated. Thanks to archival research and new testimonies, the violent seizure by the Belgian colonial authorities can now be reconstructed.

- The two precolonial forged-iron Kuba figures were part of the royal court art in Mushenge. The king gifted them in the early 20th century to a colonial official, presumably under pressure from the military conquest of the Kuba kingdom. They were purchased in 1920 by the Vleeshuis Museum through the Antwerp dealer Henri Pareyn.

- The Hemba memorial figure of a chief (singiti) was an heirloom belonging to a Hemba clan leader. How it disappeared from the community can no longer be determined, though Congolese informants point to missionary pressure. Research conducted in Congo provided new insights: a singiti means “pillar” and was always shown wearing a loincloth