In 1934, the Antwerp confectioners' association organized a competition at Jos Hakker's request to create a culinary speciality for Antwerp. Jos Hakker himself won first prize with his "Antwerp Hand" biscuit. The shape refers to the medieval legend about the founding of Antwerp: the giant Antigone demanded a right of way across the Scheldt until Brabo, a Roman soldier, defeated him by cutting off his hand. Subsequently, the port city of Antwerp began to prosper thanks to free trade.

When you open a box of the biscuits, you also discover the story of Antigone and Brabo. What is often forgotten is that Jos Hakker came from a Jewish family in the Netherlands, and that he and his family were the victims of the persecution of Jews in Antwerp during the Second World War. In other words, there are many stories hidden in this biscuit.

The biography of the biscuit

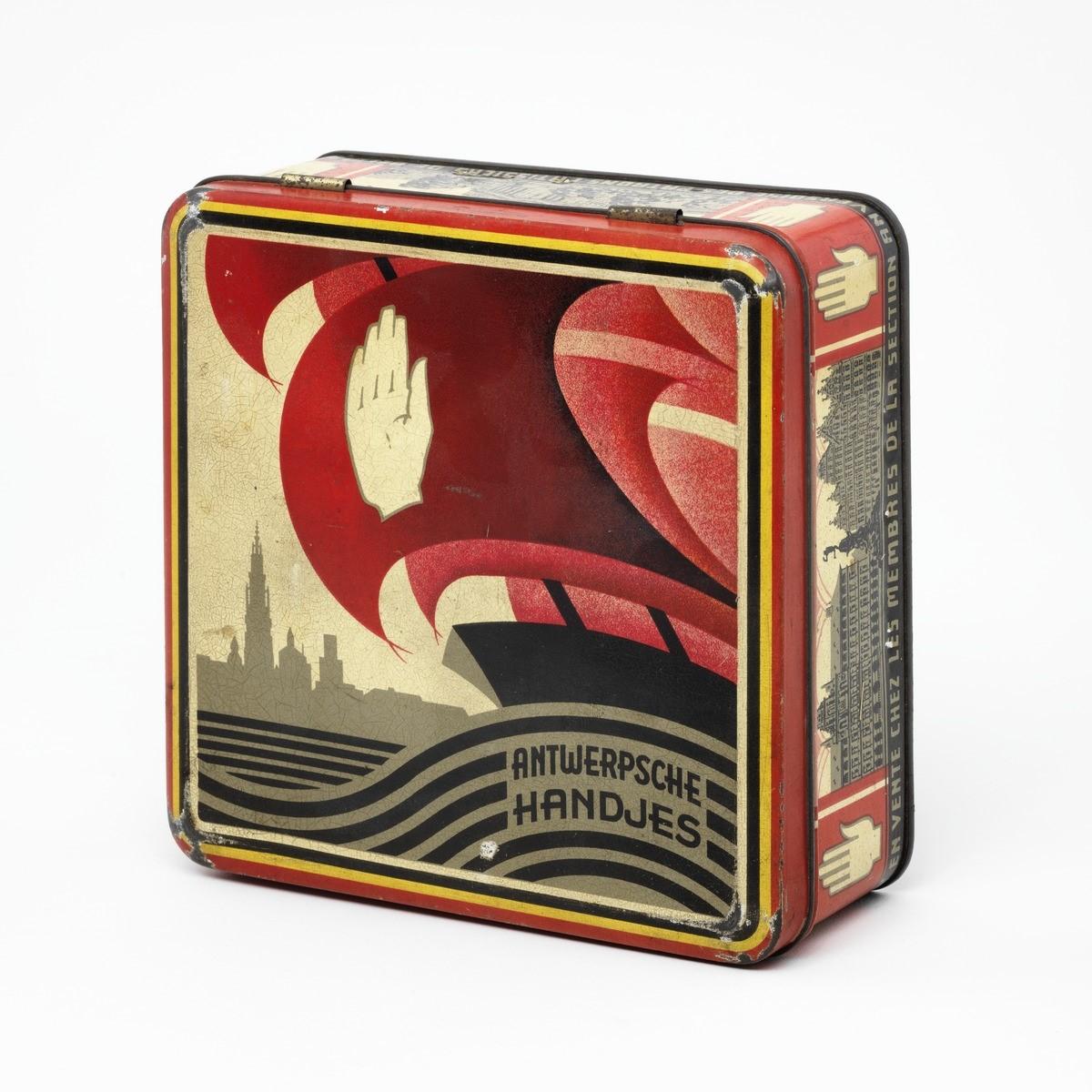

Promotional poster for the launching of the Antwerp Hands, 1934 (Collection of Jan de Kinderen)

In 1934, with the new little biscuit, the Antwerp Master Confectioners wanted to lend expression to their occupational passion and their hospitality for visitors to Antwerp. Perhaps the economic crisis and the need for new sources of income also stimulated the creation of the new biscuit. The actual sale of the little biscuits started with a bit of delay, because people had to wait for the results of the design competition for the gift box. In addition to the typical shape of the hand, the winning design also displayed a series of notable sites of Antwerp. On 15 December 1934, the master confectioners officially brought the biscuit onto the market.

During the Second World War, the sale of the Antwerp Hand biscuits presumably came to a halt. After the war, the Antwerp confectioners were concerned about the oncoming industrialisation movement. As such, they wanted to showcase the quality of the craftsmanship of the confectioners. Six bakers from the Antwerp division of the Royal Association of Master Confectioners of Belgium decided in August 1956 to bring back the Antwerp Hand onto the market. They certified the recipe of flour, sugar, butter, eggs and almonds, as well as the shape, the name and the packaging. Only Antwerp bakers that paid a licensing fee and who followed strict conditions were allowed to sell the biscuit after this.

Students of the INCOPA (now PIVA) training for bakers are baking the Antwerp Hands on the Meir and handing them out free of charge, Antwerp 20-23 October 1956. Collection of Provincial Institute PIVA

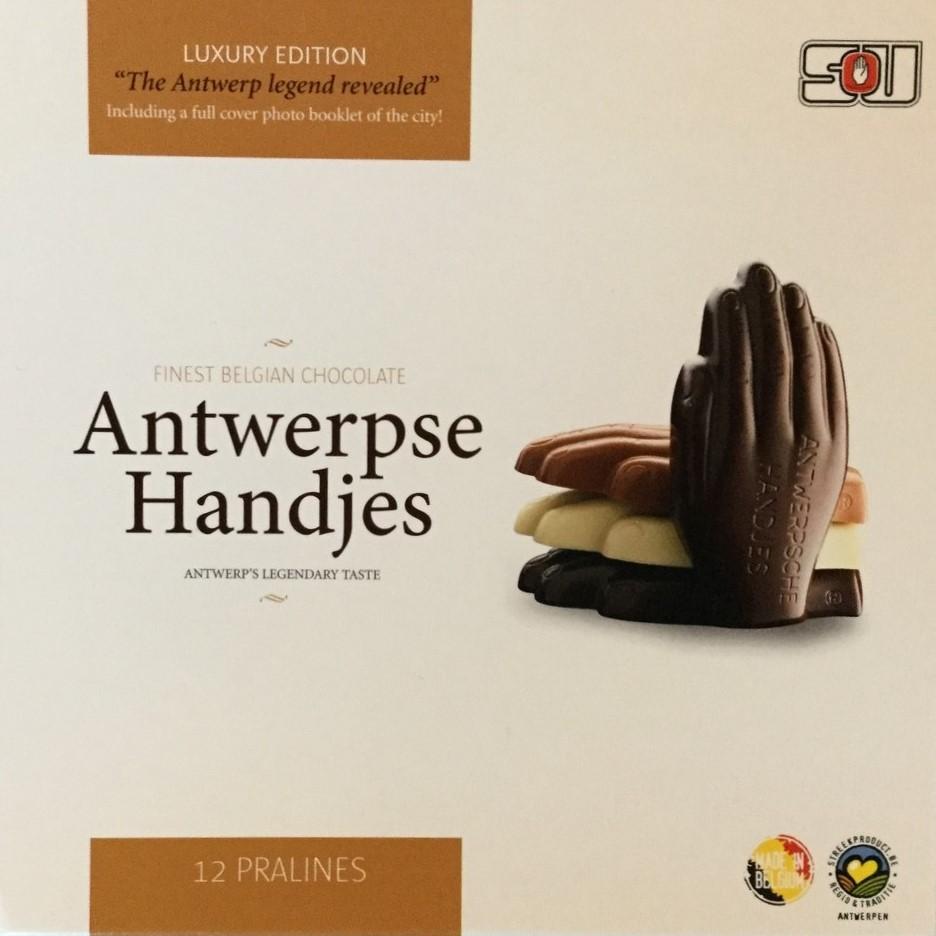

The shape of the Hand evolved over the following decades. The little biscuit became smaller and more streamlined. The almond slivers were limited to the wrist. The boxes and little bags also went through some changes. In 1971 solid chocolate versions of the hands appeared: the so-called 'caraques'. At the behest of the Syndicate Union for Bread, Pastry, Chocolate and Ice Cream industry, the firm Gartner designed a hand-shaped praline with praline or coffee filling after this. And finally, in 1982 the chocolatier René Goossens infused a chocolate version with marzipan filling with the Antwerp liqueur Elixir d’Anvers.

The Antwerp Hand biscuit grew into being a popular product for the tourist market. In 2005 the tourist service of the City of Antwerp, the industrial chocolate industry Andes (from Puurs, near Antwerp) and the Syndicate Union together introduced a streamlined make-over of the packaging. Since then, the difference between the industrial and the artisan biscuits is less visible for the consumer. A multilingual information card with the focus on the legend of Brabo and Antigoon was eventually added to the boxes.

Around the same time, under the impetus of the new non-profit organisation 'Streekproducten Provincie Antwerpen', an application was submitted to VLAM (Flemish Centre for Agro and Fisheries Marketing) to have the biscuits recognised as a Flemish regional product. That recognition came in May 2006. To celebrate, the bakers again handed out biscuits on the Meir. In 2008, VLAM also recognised the all-chocolate Antwerp Handje, the 'caraque', and the chocolate version with Elixir d'Anvers filling from chocolatier Goossens as Antwerp regional products.

So from the 1950s, sales of the Antwerp Handje biscuit became really successful. The biscuits were also increasingly considered Antwerp's heritage. At the same time, the history of the biscuit and its inventor became less and less known. Especially when the biscuit and its chocolate variant were recognised as a regional product in 2006 and 2008, it is striking that the recognition dossier and press articles are very brief about the history of it.

The biography of the creator

Jos Hakker and his granddaughters Rafke (Rachel) and Joyce Hakker. Beginning of the 1950's. Kazerne Dossin, Hakker Collection, KD_00362_000007

Who was Jos Hakker, a governing member of the Antwerp Master Confectioners and who in 1934 created the little biscuit? We are basing our information here on the research of the Kazerne Dossin Museum and the witness accounts of Rachel and Joyce Hakker.

Jos Hakker was born in Amsterdam on 28 May 1887. After the death of his father in 1889, the children were taken to an orphanage and there Jos grew up with his two brothers. Their choice of studies was rather limited and Jos was trained as a pastry and confectionery baker.

Once graduated, Jos moved to Antwerp where he had distant relatives, the Simons-Kahn family, who owned a bakery. He could work there in the business and he also met his future wife, Rachel Simons, who came from the Netherlands to Antwerp on a family visit. The couple married and opened their own pastry bakery in the Provinciestraat. They had one son, Simon Hakker, born in Antwerp on 7 September 1912.

Jos Hakker was a first-generation immigrant, as were many Jews in Antwerp at the time. The Jewish population in the city was indeed sharply increased within a very short period of time: from a couple of hundred Jewish inhabitants before the last quarter of the nineteenth century to approximately 35.000 at the advent of World War II.

In the 1930's, there were at least four Jewish bakeries found on the Provinciestraat, of which three were kosher (under the supervision of a rabbi). The fourth was the pastry bakery of Hakker-Simons whose clientele was predominantly Dutch-Jewish and non-Jewish. Around St Nick's and Christmas, there was always special pastry and sweets. The Hakker family remembers the Provinciestraat as being a lively street where Jews and non-Jews lived together cordially. There was a concentration of orthodox Jews such as in Poland, but there were also non-Jews and non-orthodox Jews living in the area as well.

The Hakkers had a great deal of contact with their non-Jewish neighbours: the non-Jewish butcher across the street, the Dutch fishmonger, the couple with the grocery store. The neighbours were friends and mutually customers with each other. In addition, Jos Hakker was involved with the Socialist Party, with which he became a member after his arrival in Belgium in 1903. From 1912 he was a governing member and starting in 1918, he was the chairman of the Socialist Party of the sixth and seventh Districts of Antwerp. Hakker also provided catering for the city and was thus highly engaged and integrated into the city. At the same time, he held firmly onto his provenance: he spoke exclusively "Holland Dutch" and would never dare to speak a word of Antwerp dialect.

World War II and the persecution of the Jews

In May 1940 Simon Hakker and his fiancée Phyllis Wach fled with the parents of Phyllis to France, as did other Jews. Phyllis’s father was arrested there in Lyon. On 2 March 1943 he was deported from Drancy to Majdanek and didn’t survive the war. Simon and Phyllis and her mother returned to Antwerp after the arrest, but fled anew in August 1942. They also took three Jewish children from the neighbourhood with them. After a difficult journey, they reached the Swiss border and survived the war.

Up until the summer of 1942 Jos Hakker had not been overly concerned himself, not even when wearing the Star of David was imposed, which he indeed described as especially stigmatizing: "Although my family never lived as Jews, and most people did not even suspect our Jewish heritage, we were still obliged to wear the Star of David with all the disadvantages that were connected with it. Personally, I almost never wore this star.” Two clear warnings made Jos Hakker realize the seriousness of the situation: the first major razzia on the Jews in Antwerp that took place in the night of 15 August into the 16th of 1942 and the warning on 22 September 1942 by a former classmate of his son Simon Hakker.

Jos let his terminally ill wife be admitted to St Erasmus hospital on 16 August 1942. After her death on 29 October 1942, he fled Antwerp. He tried to secretly reach Switzerland to join his son and daughter-in-law. His “passeurs”, contact persons who helped with his flight, were, however, collaborators of the Devisenschutzkommando: Hakker was betrayed and arrested. After two weeks in the prison of the Begijnenstraat in Antwerp, he was delivered to the Dossinkazerne (barrack) in Mechelen on 12 November 1942.

On 15 January 1943, transport XVIII and transport XIX departed from the Dossinkazerne. This was the first convoy since Jos Hakker's arrival. Registered under the number 247 Jos Hakker was placed on the deportation train with 1623 other people to Auschwitz-Birkenau. In total, 1557 deported people arrived at their destination. Sixty-seven of them were able to jump out of the third-class carriage, amongst them was Jos Hakker.

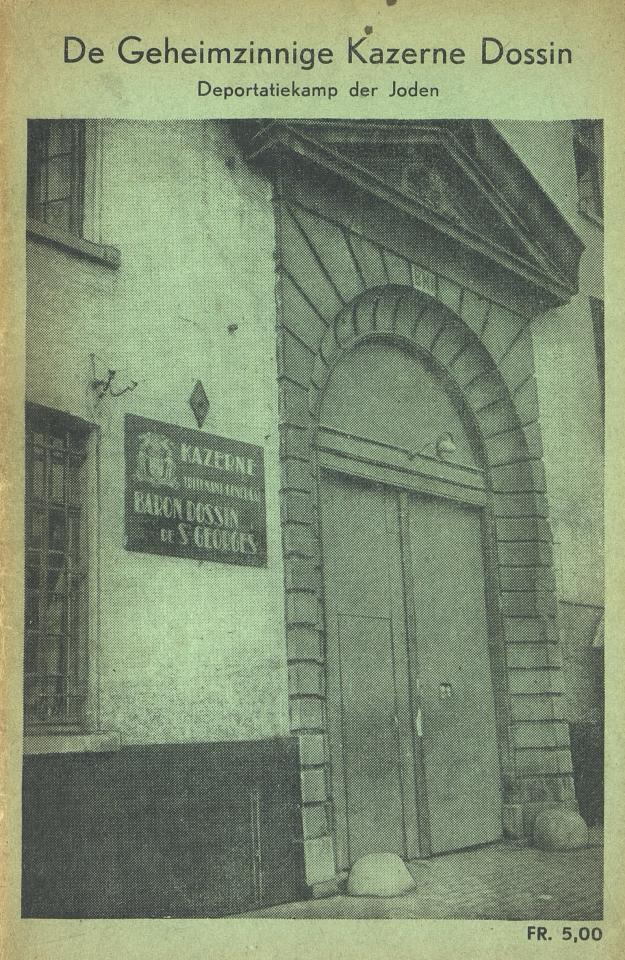

Hakker survived the rest of the war in the French-speaking part of Belgium and joined the resistance in Liège. Immediately following the Liberation of Belgium, he published his eyewitness report 'The Secretive Kazerne Dossin-Deportation Camp of the Jews'. With his highly detailed description, Hakker, as it were, became the chronicler of the Dossinkazerne.

The Hakker family after the war

Quickly after the liberation, Jos Hakker returned to Antwerp. Jos's son Simon, his daughter-in-law and his two granddaughters, whom he had never met, would return then in the summer of 1945. Together, on 17 September 1945, they reopened their pastry bakery from the Provinciestraat. That wasn't easy: aside from a few items, everything from the former bakery was gone. Moreover, it was not just starting back from scratch again, for years it was financially very difficult because during the war so much capital had been lost and in addition, a compensation had to be paid to Switzerland for their stay during the war.

The Hakker pastry bakery remained, even though it was a non-kosher bakery situated in the Jewish neighbourhood. People came there for the Dutch specialities, such as sausage rolls, ginger and almond boluses with warm ginger syrup, butter-cakes, almond cakes, filled cakes, iced cakes, Weesper cakes, meringues, Jan Hagels (Dutch cookies), currant buns, apple turnovers, apple dumplings, and currant bread with almonds and candied fruit. For the Saint Nicolas celebration, the Hakkers baked, just as before, all sorts of goodies amongst which were gingerbread men, marzipan fruits and animals, as well as the alphabet in Dutch letters. The Christmas period also meant a specific offering. In January 1956, moreover, Jos Hakker asked the Antwerp Folklore Museum about more information about the 'Lost Monday'-tradition. Perhaps that fit in with the search for a targeted offering for the Antwerp public.

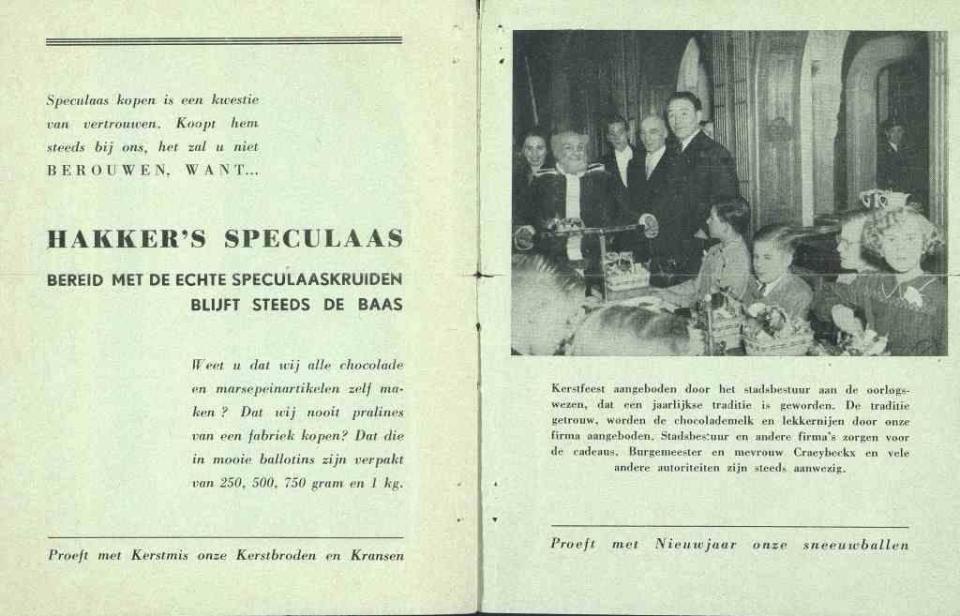

Hakker also got involved in the Royal Association of Master Confectioners and the Socialist Party again. The family was well-known in the Antwerp socialist milieu and thus with Lode Craeybeckx and Camille Huysmans, but also received visits from the Dutch Minister Willem Drees in the bakery. Jos Hakker once again became the chairman of the Socialist Party of the sixth and seventh district of Antwerp. Jos Hakker, along with his son, also took care of the receptions at the Town Hall with the visit of King Baudouin. In addition, as the chairman of the Royal Association of the Antwerp Master Confectioners, he organized competitions, conferences and receptions at the Town Hall into the 1950s. About the war, the persecution of Jews and the fact of being Jewish was scarcely, if at all, talked about for the first two decades after the war, not even with the grandchildren. Only gradually did Rachel and Joyce Hakker begin to take up the Jewish traditions and the history of the war.

More than the story of Brabo and Antigoon

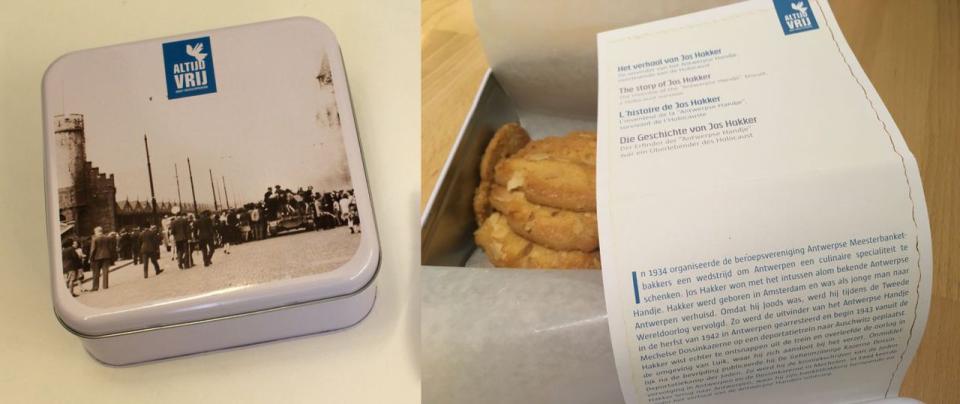

Liberation edition of the Antwerp Hands' box, with the life story of Jos Hakker in four languages

In 2019, in the context of the remembrance of World War II, the City of Antwerp issued an adapted version of the packing for the Antwerp Hands. In addition to the story of Brabo and Antigoon, the story of the creator, Jos Hakker, was also included. We hope that this initiative receives a following. Because precisely with remembering that multifaceted story, the importance of the 'Antwerpse Handjes' increases. The little biscuit can then refer to the creativity and entrepreneurial sense of the Antwerp bakers, the long history of the diversity in the harbour city of Antwerp and the resilience of the baker Jos Hakker after his exclusion and persecution.

This article is based upon the research about the Antwerp Hand by Veerle Vanden Daelen, Leen Beyers and Sofie De Ruysser: https://issuu.com/paulcatteeuw/docs/volkskunde_119_-_2018_3

See also www.kazernedossin.eu

An Antwerp delicacy since 1934: