Antwerp's lifeline

The port of Antwerp is located far inland. This location has already proven to be an advantage throughout history: it makes Antwerp a performing hub between overseas trade and the central European hinterland. But it also has disadvantages. The ever-growing seagoing ships, for instance, can no longer simply sail up the Scheldt. And historically, this location in the hinterland has another important sting: safe and free passage is essential for Antwerp to remain a port of significance!

Not only in the Antwerp city hall were the figures of Scheldt god Scaldis and city maiden Antwerpia frequently and symbolically performed. Witness the images below:

Abraham Janssens, 1609 (city hall of Antwerp)

Jacques De Roore, 1713 (city hall of Antwerp)

‘Mercurius leaves Antwerp’, Theodoor van Thulden, 1635 (Rijksmuseum Amsterdam)

Busts of Scaldis and Antwerpia, c. 1609 (MAS, AV.5529.1-2 & .2-2)

Scheldt closed? Histoire de l'Escaut

High days for Antwerp's economy when trade via the Scheldt increased during the 16th century. But as the Spaniards tighten their grip on the South Netherlands, Scheldt shipping is increasingly controlled from the North Netherlands. Eventually, the Zeelanders close off the Scheldt. Not literally; trade remains free in theory. But dues go up considerably, and on the route between Antwerp and the North Sea, ship cargoes have to be transhipped onto smaller ships twice. Such things were not exceptional on other rivers, by the way. Antwerp therefore remained an important trading centre but lost its allure as an international port because of the blockade, even though the city had already lost its attraction before the Scheldt closure due to the war atmosphere and religious disputes.

The Peace Treaty of Münster concluded the Eighty Years' War in 1648. Spain thus recognized the Republic of the Seven United Netherlands. For Antwerp, this meant that the Scheldt remained closed to sea-going ships. And that continued until the end of the 18th century.

Under the French (1792-1815) and Dutch rule (1815-1830), Scheldt shipping is again temporarily free, and each time this is cause for celebration. But with Belgian independence, the lock goes back on... However, the Belgian state negotiates a toll arrangement and pays the money itself directly to the Dutch government. This way, the port of Antwerp should not lose competitiveness. But this way of working has its price: as shipping traffic and liberalism gain ground, Belgium sees its spending increase. At its peak, as much as 1% of the Belgian budget goes to this compensation scheme!

For Belgium, it is partly the reason why it sits down with the Netherlands again. An agreement is reached for the one-off buyout of the Scheldetoll. Next, the Belgians start looking for other powers that would benefit from a free Scheldt. In the end, our country pays a third of the ransom, and 20 other countries contribute according to their share on the Scheldt traffic at Antwerp.

Thanks to growing shipping traffic, this ransom was recouped soon enough: cause for celebration!

J. P. Clays, 1863 (MAS, AS.1954.086)

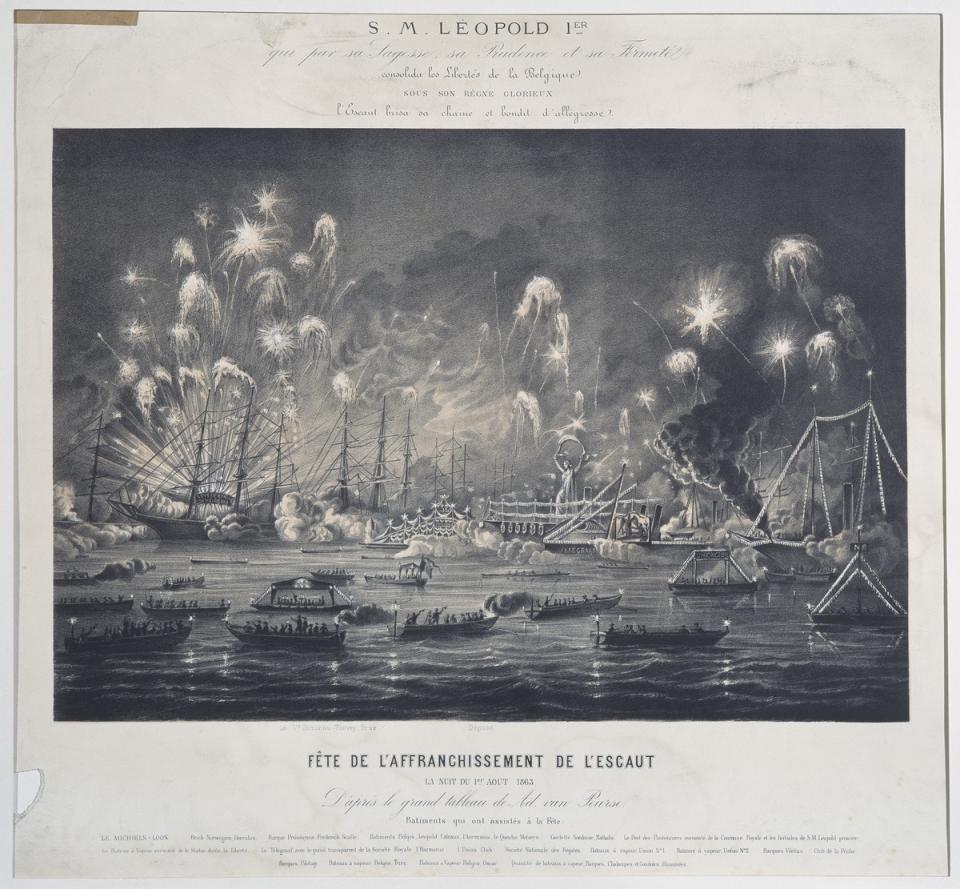

- Lithograph after a painting by A. Peurse: night party on 1 August 1863, celebrating the freeing of the Scheldt. (MAS, AS.1943.009.215) -

Festivities

Saturday 1 August 1863: on this first day in a long time, people could sail a ‘free’ river from Antwerp again. All ships on the Scheldt were festively flagged and decorated. A squadron left the docks at 11 am, accompanied by the Belgian merchant ship Marnix de Ste. Aldegonde, named after the Antwerp mayor at the time of the Scheldt closure. What caught the eye most was a gilded statue of Liberty: from a white steamer, a majestic female figure rose on the roadstead. The statue was at least five metres high and brimming with symbolism. At her feet were broken chains and a trampled Munster Treaty, and above her head she held a banderole that read: ‘La Liberté de l'Escaut - De Vrije Schelde’. The white ship was decorated with Belgian flags, and bore the arms of the countries that contributed to the abolition of the Scheldt toll. Music was played on the quays, while cannon shots echoed from the other bank. The party continued in the city with a banquet and in the pubs. The streets were festively lit up at night.

The day after, there was a parade, a foretaste of the Ommegang later that month. In the evening, a ‘Venetian night’ was planned: on the dark roadstead, fireworks were set off from ships hung with lanterns. The gilded statue of Liberty almost seemed to light up as the powder vapours rose around it. The quays were once again crowded, and rooms and even windows were rented out to watch the festival of lights as much as possible. The next day, a colourful newspaper report could be read abroad for those who were not there, because free sailing on the Scheldt was not only an advantage for Antwerp.

Clays: an unknown celebrity

We can still relive the festive event in Clays' painting. That name does not ring a bell with everyone today. Yet the man was a famous marine painter in the 19th century. Paul-Jean Clays was born on the Belgian coast, spent his childhood along the canals of Bruges and studied in Boulogne-sur-Mer. So the water and the sea were never far away, and Clays ideally wanted to become a sailor. He did indeed go sailing, but also devoted himself to his other love: drawing and painting. As a self-made man, he was apprenticed to well-known studios in Paris (Vernet, Gudin), and so he managed to combine both his loves: barely 24 when he could join a ship of the Royal Belgian Navy as an official painter. His work caught the eye at various salons, and his romantic naval paintings sold well. By 1850, he was an established painter, and over the years Clays also carried out commissions for governments. This included the painting with which he captured the ‘Scheldt Free!’ festival in 1863.

Besides this painting and an accompanying preliminary study, the MAS holds six more paintings and more than 70 sketches by Paul-Jean Clays. He can also be found elsewhere in Belgium in the collections of the Groeninge Museum, the KSMK and the MSK, among others. But his name reaches much further: the National Gallery and the V&A in London and Kunsthalle Hamburg also have works by this Belgian painter in their collections. A version of Clays' painting “Schelde Vrij” was auctioned for a whopping $40,000 by the Metropolitan Museum in New York some years ago. So let us cherish the Antwerp copy.

- P.J. Clays -

- P.J. Clays - Two barges from Heist on the beach (MAS, AS.1974.011.089) -